by Michelle Dalton EyeWorld Contributing Writer

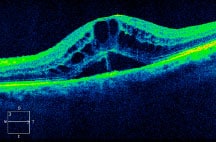

SD-OCT demonstrates intraretinal fluid, cystoid macular edema, and subretinal fluid.

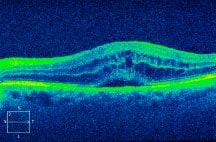

SD-OCT shows significant improvement in vision and fluid with a decrease in subretinal fluid heights.

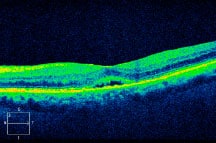

With continued treatment, the OCT demonstrates complete resolution of CME with a trace amount of subretinal fluid.

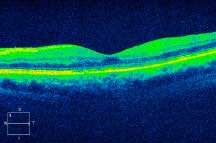

The visual acuity has improved with normalization of the retinal architecture. Source (all): Rishi P. Singh, MD

This growing population has some unique challenges for anterior segment surgeons

Diabetes affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide, and the International Diabetes Federation expects that number to reach close to 600 million in the next 25 years. More than a quarter of patients over age 65 are likely to have diabetes, and that has altered how anterior segment surgeons need to treat the cataract population. This particular subset of patients is at a higher risk for postop complications, including cystoid macular edema (CME). “When postop macular edema occurs, it’s sometimes difficult to differentiate between worsening diabetic macular edema (DME) versus Irvine-Gass related CME,” said Rishi P. Singh, MD, staff physician at the Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland, and assistant professor of ophthalmology, Case Western Reserve University. What often happens is the cataract does not allow easy imaging of the retina, so once the cataract is removed, “surgeons may find proliferative diabetic retinopathy (DR) or clinically significant macular edema that they didn’t know was there.” After cataract extraction, treating the remaining DME is of paramount importance, or the patient may not see as well as those without diabetic complications, said Rohit Varma, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology, and associate dean for strategic planning, Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “If patients have known diabetes, refer them to a retina specialist to ensure there’s no macular edema or retinopathy,” Dr. Varma suggested. “Otherwise, the postop cataract outcome may not be as good.” Poorly controlled diabetes can damage the small vessels in the retina and cause leakage of fluid that leads to swelling and a loss of central vision, yet nearly half the subjects in a recent study1 with both DM and eye damage “had not visited a clinician in the same year before the study,” Dr. Varma said.

“If they’ve had prior vitreomacular surgery or known DR or DME, there are numerous studies that show using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for a week before and two to three months after surgery lowers the risk of diabetic-related complications even in uncomplicated cataract surgery,” said Steven M. Silverstein, MD, in private practice at Silverstein Eye Centers, Kansas City, Mo. While there is limited data to suggest uncomplicated cataract surgery increases the risk of DR in those with diabetes, “we know it increases the risk of DME,” he said, and patients should be told their diabetes has put them at an increased risk of retinal swelling, with or without cataract surgery, but the cataract surgery may increase the risk.

Dr. Varma said as long as the retina can be evaluated clearly (as in the case of early stage cataract), an optical coherence tomography (OCT) centered on the macula should be sufficient. Once there is a suggestion of DME, he recommends referral for treatment before cataract surgery.

Advice in the preop and surgical periods

Dr. Singh recommends preop testing first with an undilated eye “to rule out the potential neovascularization of the iris.” Second, if the patient is interested in premium lenses such as toric or multifocal IOLs, “performing an OCT prior to surgery would be quite useful in ruling out coexistent macular edema or a significant epiretinal membrane,” he said. Dr. Silverstein follows his patients “until they require laser treatment or vitrectomy,” he said. In the perioperative regimen, he pretreats with an NSAID for one week and continues, even in a white and quiet eye, for 2 to 3 months for those with DR, “with tapering dictated on the exam and OCT if indicated. For patients with known DME in the current or fellow eye, I inject 4 mg of dexamethasone sub-Tenon’s at the end of surgery,” Dr. Silverstein said.

In a study,2 Dr. Singh and colleagues found a “five- or six-fold reduction in the incidence of macular edema when the patient was placed on an NSAID-steroid combo following surgery.” But, Dr. Singh pointed out that this was only a study of patients with existing DR. “If someone has no ocular manifestations of diabetes, there is no evidence that combination use of a steroid and an NSAID agent is necessary,” he said. He does recommend keeping patients on NSAIDs for up to 90 days postop.

“Numerous studies have found that the level of retinopathy is the key driver for the postoperative incidence of macular edema,” Dr. Singh said.

He suggested that when performing cataract surgery, “ensure there’s a large rhexis. A small rhexis creates capsular fibrosis,” he said, “and prevents adequate monitoring and treatment to the peripheral retina with laser.”

Preventing postop CME

Dr. Silverstein recommends using the “most powerful” NSAID and steroid in the postop period to prevent CME (and does not limit that to just the diabetic population). Because the two work on different points on the inflammatory cascade, using the two together has been shown in several studies to be better than using only one or the other in the postop period. “If the patient does not exhibit signs of diabetic disease in the current eye but does in the fellow eye, you should presume the eye you’re working on has diabetic disease and treat it accordingly,” he said.

Using spectral OCT has become an easy way for clinicians “to localize cysts and localize fluid in the retina very quickly,” Dr. Singh said. “If you notice macular edema and the patient has an abnormal OCT or an abnormal clinical exam that suggests he or she has edema, that should be stimulus for a referral.”

Unique issues for diabetics

Dr. Varma said the main take-home point from his study is to follow people who are developing cataract over time to ensure the retina is being examined as well. “Part of the vision loss in this group of patients may be completely unrelated to the cataract,” Dr. Varma said, especially in the early stages.

Dr. Singh believes the rate of postoperative macular edema is underdiagnosed—and believes eyecare professionals could overcome the issue by dilating the pupil on follow-up exams and performing OCTs when indicated. “Most patients with the proper identification and management of macular edema will do quite well with standard of care treatments,” he said.

In patients with pre-existing diabetic retinopathy, “you have to assume they’re at significant risk for DME, and treat the eye aggressively with an NSAID preop for a week and 2 to 3 months postop.” If he is performing a phaco-trab, Dr. Silverstein will also pretreat with an NSAID and continue for 2 to 3 months after surgery.

When systemic disease is not controlled

“Optimizing the patient systemically prior to surgery is the key to a good outcome,” Dr. Singh said. “In cases where patients have high hemoglobin A1C values, you lose nothing by referring them to their primary care physician or endocrinologist for better control.”

“We’ve had people way out of control with levels around 400 or so, but who are asymptomatic. You don’t want to bottom out their blood sugar if their body is accustomed to the elevated blood sugar level, but we do recommend following up with their primary care physician or endocrinologist,” Dr. Silverstein said.

References

1. Bressler NM, Varma R, Doan QV, et al. Underuse of the health care system by persons with diabetes mellitus and diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6426. Published online December 19, 2013.

2. Singh R, Alpern L, Jaffe GJ, et al. Evaluation of nepafenac in prevention of macular edema following cataract surgery in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012; 6:1259-1269.

Editors’ note: Dr. Silverstein has financial interests with Alcon (Fort Worth, Texas), Allergan (Irvine, Calif.), and Bausch + Lomb (Rochester, N.Y.). Dr. Singh has financial interests with Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, Genentech (South San Francisco), and Regeneron (Tarrytown, N.Y.). Dr. Varma has financial interests with Allergan, Bausch + Lomb, and Genentech.

Contact information

Silverstein: ssilverstein@silversteineyecenters.com

Singh: drrishisingh@gmail.com

Varma: rvarma@usc.edu

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us